Every Vietnam vet—of the estimated 610,000 from the U.S. Armed Forces who survive in 2023—has a story to tell. Ex-Marine William J. “Bill” Hatton recalls walking a jungle trail when, off to the side, he saw an enemy soldier with his belly opened, so that his guts lay in his hands and his lap, with a look of surprise that he was not quite dead yet. He had many more experiences that he wants to relate to others, including leadership roles in the war, after the war among Vietnam Veterans Against the War, and in economic development with a First Nations band in Canada.

Less intimate but still horrifying was the witness of journalists conveying the story back to Americans at home.

In the 1960s, Walter Cronkite, trusted news anchor and an exemplar of old-school journalism, had traveled to Vietnam, ridden in Air Force planes, interviewed U.S. troops—and ultimately arrived at a conviction that he needed to speak out against the war. Not his usual just-the-facts reporting but a call to recognize the United States was mired in a stalemate and needed to negotiate an end to the war. His opinion piece aired on the CBS news broadcast Feb. 27, 1968.

Despite seeing fleeting images taken from helicopters of green fields and dense jungles on the television, or the occasional frightening still photograph, like the one of the girl whose clothing had been burned off by napalm, for most Americans the “jungle battlefields half a world away” were very distant.

For many of those serving in Vietnam, however, the scenes were personal, dehumanizing, and terrifying. Hatton recalls a Marine pastime: “playing” with a Vietnamese man caught out in a field. First shoot to the left of him, then shoot to the right of him. Make him zigzag in fear until he falls from fatigue. “It was a horrible thing to do to a human being,” Hatton says now. “Though it didn’t seem so at the time.”

Perhaps his and the other Marines’ empathy had been so eviscerated by drugs, their own fears, and the close-up encounters with people who might or might not be enemies that “you really depart from human feelings during a war. You’re not shooting people but shooting ‘other things.’”

After the war, serving on a panel in Detroit of Vietnam veterans attesting to the horrors of war, including many war crimes, acts of cruelty, or incidents of torture, Hatton and others tried to get Americans not involved in Vietnam to hear how, as young men in uniform, they became immoral animals. As captured in the documentary “Winter Soldiers,” one young guy was asked by an officer how he knew the dead person in black pajamas was Viet Cong.

If the person is dead, he had explained to the officer, he must have been Viet Cong.

Young Vietnamese women were raped; U. S. officers were killed by “fragging,” i.e., shot by their fellow soldiers; Vietnamese people were called “zipper eyes” and much worse, before being dropped from U.S. helicopters to the fields below. As Morley Safer reported on CBS news in 1965, Marines were filmed torching all the homes in a village, Safer said, “leaving the villagers with nothing.”

Fifty years after the United States’ official involvement in the Vietnam War ended in 1973, with the conclusion of the Paris Peace Talks, Bill Hatton remembers how he obeyed orders as a young Marine. Fight the war now, he was told; protest it later.

And, immediately upon his discharge, he did. Along with leaders of the Black Panthers, like Angela Davis, he organized the first-ever protest march of active-duty armed forces against the Vietnam War, in Oceanside, California.

A Buddhist haven in the Veterans’ Home

In 2023, Hatton resides in the Minnesota Veterans’ Home in Minneapolis. Other than the workout room’s tunes from the 1950s and 1960s, it’s rather quiet. Once in a while, the overhead PA breaks in, announcing the passing of another veteran. The disembodied voice asks those who remain to remember their comrade.

As the announcer speaks, Hatton prays, repeating three times the mantra he learned to request for a dead or dying person a favorable rebirth, in accord with his adherence to Tibetan Buddhism.

Certainly many of these veterans will need a boost into their next lives, as they had arrived at the Veterans’ Home hate-filled, in pain, or with minds long wandered elsewhere. Hatton came here, angry as hell, about five years ago, after being ousted from other nursing homes because of his combativeness.

Hatton’s room is lined with thangkas—depictions of Tibetan deities, spiritual creatures—colorfully vibrant, sometimes high-stepping, perhaps dancing. They appear to move, much more than Hatton, who is (other than his right hand) paralyzed after five strokes, a delayed impact of his experiences in Vietnam, sleeping eight miles from the Demilitarized Zone, under blankets of Agent Orange, a defoliant to strip the jungle that hid Vietnamese combatants.

“The country was poison to us, and we didn’t know it,” Hatton says now. While for most of his life he has been an enforcer, a fighter for justice, and an organizer to improve people’s lives, the legacy of his time in Vietnam remained painfully alive and lashed him with memories. He needed to “protect” himself with guns, he thumbed his nose at established authority, and he strove to understand Vietnam and other, earlier wars.

His first wife supported his anti-war activities but found him hell to live with. Hatton has been married three times and divorced three times. He has one child, a son, Alaric, and a granddaughter.

Only in the last five years or so has he found some peace.

Finding a friend

One of the contributors to his peace is his friend Elena Geneja. She grew up in Hoyt Lakes, on Minnesota’s Iron Range, and married at 19. Sadly, her first husband was abusive. She escaped from Northern Minnesota to the Twin Cities, where she was hired to sing in local eateries and bars.

She remarried, happily. Husband Glen Geneja urged her to become a nurse, so she went to school for the degree. When he was laid off later in their lives, Elena Geneja encouraged Glen, who was kind and compassionate, to become a nurse, too. He worked at the Minnesota Veterans’ Home for a few years before he retired.

Then her husband needed thrice-weekly care for his diabetes-related condition; an ambulance would take him away for several hours of treatment. After she retired, she had some extra time and came to the Minnesota Veterans’ Home to volunteer.

In conversation with two Veterans’ Home volunteer coordinators about how she might serve, Geneja saw them look at each other. “We’ve got the person for you.” Seeing her age—in her 70s—they thought she might be able to tolerate Hatton. “‘It will be a challenge,’ they said,” Geneja remembers. “‘He’s been in the war, and he’s had a hard life. A lot of the soldiers take it out on everybody.’”

She tends to accentuate the positive. “I thought: ‘It will just take some time.’” She was warned, however, never to ask him about the Vietnam war.

After a few months of visiting Hatton, reading to him from books he requested, she finally asked him to stop using the F-word so often. He looked at her, a bit surprised, then conceded. He began to level up his rough Marine-influenced vocabulary—a bit.

Then one day, he said: “Why haven’t you asked me about the war?”

“They told me not to!” she replied. He proceeded to talk about Vietnam, and she heard from him stories of children dying and human blood dripping from the trees—the remains of soldiers blown up by mines. Vietnamese troops ran headlong into a semicircle of automatic weapons’ ammo fired by Hatton and his fellow Marines; the enemy didn’t have a chance of surviving the onslaught.

Although horrified, she was a conscientious, sympathetic listener who asked many questions. Hatton’s post-Vietnam career focused on economic and community development, so in turn he helped her with financial concerns and other advice. Says Geneja: “We’ve ended up real good friends.”

With their growing trust, Geneja has someone who needs her help. And, adds Hatton: “My first wife helped keep me alive. That role is what Elena plays now.”

Roots of the Vietnam conflict

Hatton is a student of history, particularly of wars. As he will tell you, the conflict in Vietnam began long before the Marines—and Hatton—arrived. The main rope in the braided early 20th century history of the country, then called Indochina, was the colonial power of France. During Japan’s imperialistic advances in the late 1930s and early 1940s across many countries in Asia—Korea, China, and Indochina—French diplomats asked the U. S. government to help protect French colonial interests in their colonies.

Before and during their involvement in World War II, the United States diplomats did assure the French of their future support (see part 1 of the Pentagon Papers), while simultaneously upholding in international agreements the rights of national self-determination. For a time, U. S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt floated the idea of an international trusteeship for then-Indochina. After WWII, the French increased their fight to reclaim their colony, while many of the Vietnamese people fought back.

During the 1950s, the United States sent military and CIA advisors to support the French-backed government of South Vietnam. The 1954 Geneva Accords, which included the French, set up the 17th parallel as the “border” between North and South Vietnam. But, Hatton notes, it wasn’t just Ho Chi Minh and his followers who objected to the French; “a lot of people in South Vietnam wanted to be free of colonial powers.” By 1958, things were “boiling up,” says Hatton. The United States sent a Marine helicopter unit to Da Nang. Says Hatton: U.S. involvement was “not concealed anymore.”

Hatton’s war

During firefights, incursions, and war escapades, including ordered but illegal and long unacknowledged forays into Laos to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail that supplied Viet Cong in the South, Hatton found his fellow Marines often a bit brutal, cruelly sarcastic, and deeply cynical. While someone was preparing for combat, the others would say, “You’re not going to make it. Give me your Black Book!” After all, Hatton says, “Who wants to leave their girlfriends lonely?

Yet the ties that formed among the men during the war were profound and long-lasting. “The Marines are your brothers,” Hatton says. After Vietnam, they helped him time and again, from supporting the ACLU efforts to try (and fail) to reinstate him in his local government job, to finding housing, to guarding him against neighbors who threatened him and his wife, and, in the time since his paralysis, cleaning up an accident of incontinence that he, paralyzed, couldn’t deal with.

These days, he supports other veterans financially through the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation. He also sends aid to an orphanage in Vietnam, with the help of his Buddhist friends, and regularly gives money to nuns in Tibet, who in turn pray for him. He’s a generous man, says his teacher of Tibetan Buddhism, Lama Yeshe. Generosity is an important virtue in Tibetan Buddhism. “Little by little,” says the lama, “he’s making progress.”

It was not always so. Years earlier, after heavy and regular indulgence in high-test pot (grown with seeds he carried from Vietnam), speed, and tabs of LSD, he went to the emergency room with his heart beating an astronomical 330 beats a minute. From there, he was sent to drug rehab. He also declared bankruptcy twice, unable to cobble together enough money driving taxis around the Twin Cities and other jobs he picked up to keep his household afloat.

In the Marines, he was called a “sea lawyer”—not a compliment—because he read the code of the Corps with care, figuring out ways to wear uniforms outside the norm or sport a mustache, yet staying within the rules. As someone who had been educated in a Roman Catholic seminary, then returned to a public high school, and who had enlisted in the Marine Corps but liked to tweak “superiors,” his strategy was to keep a straight face. If the powers suspected him of flouting the rules or being disobedient, he says they would have punished him. The Trickster mindset may have helped him in his later career; it definitely encouraged him to know the rules in any situation so that he could bend them.

After losing his job, he left Bagley. He found assistance from the State of Minnesota to complete his college degree at Metro State University. Hatton became certified as a industrial development specialist and started down a new path. The long tail of Vietnam, however, was still attached and, once in a while, lashing him.

Leaning into war

“When we were kids, we were always playing war,” he says now. Hatton’s mother was a nurse in the Army Nurse Corps during WWII. Early on, he adds, he “got the impression that you weren’t a man if you weren’t a veteran.”

Being the eldest of four sons growing up in a working-class neighborhood in an industrial city in Indiana may have prepared Hatton to fight. His dad was a member of the steel-workers union; at an imposing 6 foot 5 inches, he was sent around to collect union dues, usually successfully.

Hatton inherited his father’s spirit of organizing to improve situations. During one picket line, Hatton’s father jumped the fence and plugged the union coffee pot into the company’s electrical outlet, to help fuel the strikers. He was cheered by the workers on the line.

Although he defended his brothers with his fists, he also was a devoted reader as a youngster. The history and literature of an earlier age about previous wars introduced him to warlords, royalty, and nations’ leaders who sought the upper hand in battles over religion, trade, or territory. He was and is fascinated by operational details, these days following closely Ukrainians’ battles against invading Russians.

But for the United States, the war in Vietnam was a different game: it was an accountant’s conflict. What was the body count for that day? How many pieces of ammunition were needed to stall that North Vietnamese advance? Were the U.S. troops killing efficiently?

“Joining the baddest-ass street gang“

But Hatton did not know these behind-the-scenes calculations as a 17-year-old Marine stationed in Honolulu.

As a kid, Hatton was “dazzled by the uniforms and also the reputation of the Marine Corps. They were like the baddest-ass street gang in the world.” About 10 years later, at an age when he could have been drafted into the U. S. Army, he instead chose to enlist with the U.S. Marine Corps.

In Hawaii, he had a serious assignment, to monitor nuclear weapons. But he wanted more—to really prove oneself as a Marine, one must experience combat. He applied nine times to go to Vietnam before his officers agreed to send him there.

Trained as a heavy equipment mechanic, Hatton arrived in Vietnam to maintain generators, run bulldozers, and supply a counter battery radar. He was given three days to acclimate. “I knew almost right away that we were in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

One way he could tell: “We got shot at by the South Vietnamese: our gallant Southern allies.”

A diaphragm of twisted snakes

After Vietnam, Hatton gradually moved from a walking dead veteran back to living and leading a life of meaning; it took time. Like his fellow Marine, the late Vietnam veteran and Anishinaabe poet Jim Northrup, Hatton realized “surviving the peace was up to me.” [BOMB Magazine | Shrinking Away]

Having graduated high school from Bagley, Minn., population 1,340, Hatton returned there after his discharge. He married, moved in with his wife’s parents, and gained a local government job. And, because of the kind of Vietnam vet that he was and is, Bill Hatton was in the job only a few months before he was fired.

His first wife described him as having a diaphragm composed of twisted snakes: Not easy to live with. But she supported his activities against the war.

He proposed that Bagley host a huge music festival, something akin to Woodstock but out on the western plains of Minnesota. Hatton says he lined up big names—among them, the Rolling Stones, Jefferson Airplane, and the Royal Winnipeg Ballet. But when his fellow citizens heard of the plan, local bigwigs protested. He lost his government job.

As Star Tribune reporter Robert Hagen wrote in an Aug. 29, 1971, article: “Friends guard fired planner after he unites Bagley—against him.”

Hagen quoted Hatton defending his advocacy against the war. “People are always willing to sit back and believe something is being done when it isn’t,” said Hatton. “I can’t do that. I have to get involved—I have to.”

Already in dire straits with no job, Hatton heard from his father-in-law that some of his old high-school classmates were going to shoot up his and his wife’s mobile home. Hatton figures the “John Birchers,” as he calls those guys, miscast him as a hippie. Instead of running away, Hatton called up his Vietnam veteran buddies, asking them to come north, bring their guns and ammo, and help him defend his home.

They came, armed.

The local sheriff was not pleased. He told Hatton to disband his guard, after offering him no protection. Finally, after his friends were considering developing killer teams to track down Hatton’s opponents, Hatton instead suggested they go back home. No firefight this time.

Now, he remembers with a chortle the rock’n’roll and cultural extravaganza that might have been in Bagley, bringing tourists and their dollars. Stymied, he redirected his energy to another organization, Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW).

Along with local writer and fellow Vietnam veteran Chuck Logan, other Vietnam vets, and celebrities like Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland, Hatton helped arrange for guerilla theater actions in Minnesota. Stops in towns along a route from Northern Minnesota to the Twin Cities were designed to give ordinary people a taste of the experiences in Vietnam, with actors planted in the crowds to re-create feelings of terror.

“We had the conviction that we had to bring the war back home,” Hatton says. “I still have that conviction today.”

Hatton also joined the Winter Soldiers, a group from VVAW, who in 1971 and 1972 testified about their transformation by the war—how it turned them amoral, unfeeling, all too capable of committing war crimes. They wanted no more Americans to have these horrific experiences.

Members of the media attended a panel discussion and gathering in Detroit that evolved into a 1972 protest march in Washington, D.C.—one remembered by many as the time and place veterans threw back their combat and service medals. Hatton mentions that then-Senator Hubert H. Humphrey met with some 200 veterans from Minnesota.

During his time as an anti-war activist, Hatton debated representatives from Veterans for a Just Peace; his opponents argued that the Americans had abandoned their South Vietnamese allies. Some even asserted that the Americans and South Vietnamese had already won the war, even though the Paris Peace Talks had officially ended U.S. military involvement. Other veterans came home and said very little: They had done their duty as they saw it.

“It was the beginning of the culture wars that we are still fighting today,” he says. Hatton and other veterans called for “not one more death; not one more wounded.” Yet, coached by Floyd Nagler, another former Marine, who after the war became a leader in veteran affairs in Minnesota government, Hatton ended up joining the Marine Corps Reserve.

“I was never a hippie,” he emphasizes. Even when he and hundreds of other veterans traveled to Washington, D.C., to testify against war crimes, including their own, they were essentially conservative. “It was a screwed-up war,” Hatton says, “and my buddies agreed we needed to get out.”

Fear and tedium

About 10 years earlier, while serving as a Marine in Vietnam, Hatton saw the rules of war dissolve—rules he had learned during his U.S. Marine Corps training and from his personal immersion in military history and heroes. In Vietnam, the too-often apparent chaos amid secret forays, the armed forces’ bookkeeping by body counts, the brutality witnessed by him, and also caused by him, broke part of his heart and stole part of his spirit.

“We thought we were going to win with firepower and racking up the body count,” Hatton says. “But they were fighting for their land.” The Vietminh, he adds, were “treated as insurgents when, in fact, they were patriots.”

In the Marine Corps, he adds, “someone points a weapon at you horizontal, you just blow them away.” Like author Martin J. Dockery, an advisor in Vietnam, Hatton learned to shoot when everyone else shot. (Dockery’s memoir from his time in Vietnam in the early 1960s is titled “Lost in Translation.”)

“All that was needed was for one soldier to start shooting, then all those around him would shoot in the same direction. They did not need to see a target, because they all felt in danger,” Dockery wrote. “I found that I was no different.”

Fear and tedium were countered by Hatton and many others with pot and speed: “I smoked dope so that I would feel better,” he says. “I would take speed so that I could function” as a proper Marine. He adds that speed greatly reduces soldiers’ empathy, as the Nazis had found dosing their troops during WWII.

Hatton’s testimony as part of the Winter Soldiers panel in Detroit and the protests in D. C. that followed about his illegal and immoral killing were later repeated in Life and Esquire magazine coverage.

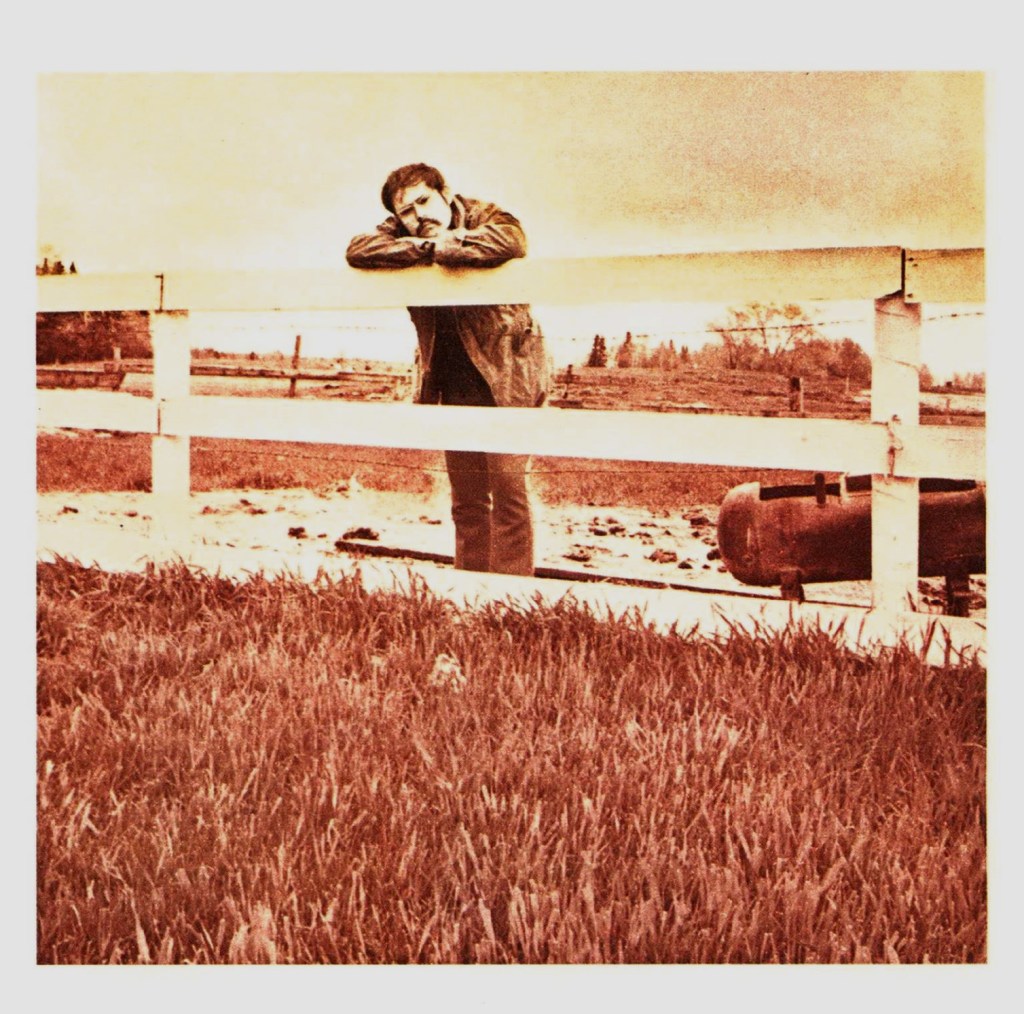

Bill Hatton, taken by Benno Friedman

for Esquire magazine, October 1971.

His war crime was propelled by his annoyance at a little local kid who every evening berated the Marines while they patrolled their Vietnamese base as a group in the back of a U.S. vehicle. The Vietnamese boy called them “number 10,” the bottom of the barrel, and threw small stones at the squad. Peeved, perhaps afraid of an ambush, Hatton led the men in a revenge attack. They gathered big rocks before one night’s patrol and, when the boy yelled out, the Marines threw the rocks at him.

After the barrage, all that remained were some bloody shorts. The horror he had organized fled Hatton’s conscious mind; it was not until years later, prodded by a war crimes inquiry, that he recalled it—and quailed from it.

No peace

Having done his best with his testimony to make his fellow Americans pay attention to the atrocities committed by troops in Vietnam, Hatton returned to Minnesota. Following the war, Hatton carried a pistol in the back of his belt, bringing it to Bemidji State College and other places. Once, he pulled it out to harangue a janitor.

“More and more I realized the gun had become the ‘solution’ to my problems,” Hatton says. “And that wasn’t right.”

At the same time as the Vietnam War, Americans at home and abroad were carrying on a war against drugs, and conflicts arose between the Black and white races.

“Vietnam left you with no peace—not in the rear, not anywhere,” Hatton says. “You were always on the alert.” He was tailed, wherever he went, by horrors of the war.

A road out, through community development

Hatton was given a job in the Minnesota Department of Economic Development in St. Paul. He visited 500 cities to propose initiatives for community development based on the locals’ needs.

One of them was on the White Earth reservation; Hatton’s van was “borrowed” by some young men for a joy ride into a nearby town.

While he waited to get his van back, Hatton decided to track down some of the excellent Native beadwork that he had heard about. He was referred to an elder, Frances Kianna, a woman who wove baskets from black ash. He bought a basket from her and explained his predicament, trying to persuade people to follow his guidance and better build up their local economy. As it turned out, he had called upon a higher power: an apparently quiet elder.

The next day, he went to the tribal council. The van had been returned, and the men, young and old, were ready to listen to Hatton. The basket maker was a key connection with her community for Hatton. Given his tough mother and his adamantine grandmother, he already had respect for women; now he became convinced that most Native nations were matrilineal, with women holding great power.

After a few years, he decided to bring his community economic development expertise north. Flying to Northern Saskatchewan for a job interview, Hatton looked down on the mosaic of lakes and felt the pull of home—a new home. While he was growing up in a Northern Indiana industrial city stinking with air and water pollution, he could hardly have imagined such natural beauty, wide-open spaces, and few barriers to the cleansing winds.

Now in his 30s, he was determined to find a job and a place for himself there working with First Nations and Metis people from the area. Having already served as a consultant for the provincial government for a year, he began to see this frontier as a place that he could make a difference—to create value for people, especially Native people, who had their resources and benefits stolen and seen promises made to them broken for decades and centuries since the colonizers arrived in North America.

Applying for a business development job in La Ronge, Saskatchewan, Hatton brought with him expertise advising underserved communities he had learned in Minnesota.

After serving poor women and families in Minneapolis for several years—he also had a position on the Minnesota Indian Affairs Commission—Hatton switched to a new operation. His company developed war simulations for much less cost in time and ammo and personnel to help train combatants. Not only did he and his team run simulations for U.S. forces, they also were contacted by foreign governments. The FBI and the CIA were concerned that Hatton and team were naive and could accidentally aid another government against the wishes of the United States.

Hatton, not a person who kowtows easily to authority, tired of the agents turning up with different stories, offering diamonds for payment that he could not cash in, and introducing new people trying to infiltrate their successful enterprise. He wanted to break out from under intense surveillance with his current company.

His second wife told him he had changed; he had become an asshole.

Seeking help, he ended up with a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He was diagnosed and treated in Minneapolis by PTSD expert Jeremy Boriskin. “He told me not to go anywhere or do anything,” Hatton remembers. “They want to treat it like it’s a car accident,” he adds, which Hatton believes is not enough to erase memories of human blood and body parts dripping on him from jungle trees.

So he decided to move. His plan, as he explained it to the First Nations and Metis (Natives who also were part French or part Scottish) was to create the “best Indian economic development organization that ever existed.”

“That was not close to true, but they believed it,” he says, which was the essential factor in their growing success. Just as he had learned in the Marine Corps, Hatton wanted the First Nations band to aim high.

He notes with admiration that in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Metis were like the Teamsters of the 19th and 20th centuries: They invented the Red River cart, which allowed them to harvest multiple carcasses of buffalo. Compared with being able to haul part of a buffalo by travois, as other Native peoples did, this cart practically industrialized buffalo hunts, according to Hatton.

Hatton consulted with a Crown Development Finance Corporation in Saskatoon and then with the Bella Coola and other First Nations peoples. His previous encounters meant, he says, “I wouldn’t have to be trained to get along with Indians.”

Hatton’s expertise was in building administration institutions to implement economic development. So, rather than taking grants from the government or foundations, Hatton and his colleagues in the Lac La Ronge Indian Band set up the Kitsaki Development Corporation; he served as controller and general manager.

“I was generally viewed as an asshole,” he says now, “because I had no respect for big merchants parading around…[nor] the Gods of Philanthropy.” He sought equity for the First Nations and Metis, built opportunities for employment, and kept the stewardship of the land as a priority. When the development corporation bought the hotel, they made the Lac La Ronge Indian Band the biggest landowner in town, which brought them pride as well as economic benefits.

Kitsaki has made progress since its founding in 1981. A related website reports: “The band of 8,000 First Nations people, living in six different communities, owns or jointly owns 30 companies and 12 businesses, including a hotel, a catering company that services the northern forest and mining industry, a trucking company and beef jerky and wild rice production ventures.” Hatton says that when he arrived, the local First Nations and Metis people chose to walk around with their heads down. Over time and with successes, they straightened their backs, became stronger, and looked ahead, literally and figuratively.

An intense focus on work, no drugs—“it required all my attention to make things good”—and his striving to make the corporation self-sustaining and successful kept Hatton engaged. “I was able to create value for people, which I really liked to do,” he says. Still, “I was always looking for a way to take refuge.”

Even though northern Saskatchewan might have seemed far enough away from Vietnam, Hatton says, “It’s always with you.”

Homecoming

Visiting the United States to see his third wife some 10 years ago, he had a stroke. Without money for an air ambulance, he could not return to Canada. He was cared for in more than one nursing home before he came to the Veterans’ Home.

Now in his 70s, Hatton says: “In my head, I’m still 23.”

Today, as he speaks to visitors from his high-tech wheelchair, he faces a vertical display of his Vietnam War combat veteran ribbon, his sergeant’s stripes, his badge of membership in the Bigstone Cree Band, a shiny Marine Corps globe symbol with anchor and eagle, and a Buddhist prayer. “Until I reach Enlightenment I take refuge in all the Buddhas and in the Dharma and the Sangha….”

Lama Yeshe remembers that when he first met Bill at the Kenwood nursing home, he had models of war equipment set up all over his place. “Eventually, without me saying anything, those went away,” says his teacher of Tibetan Buddhism.

Hatton, who was raised in the Roman Catholic church and attended seminary as a teenager, says that when he was about 12: “Where I wanted to go was to go to God. …I wanted to be the holiest, wisest man in the world.” As he grew older, he rejected the Roman Catholic church as too beholden to the Roman Empire, feeling that Christianity had changed from a band of believers spreading love to an official church imposing hierarchies on ordinary people. While in Vietnam, Hatton says, he was “psychologically at war between a Marine sergeant and a devout Buddhist.”

Though most of his in-country memories haunt him with blood and fear, those wartime circumstances offered the occasional surprise. He tells of Vietnamese kids who came over the hill while his Marine squad was setting up the weaponry to defend themselves during the night. The youngsters scrabbled down with ice-cold Cokes and still-frozen Popsicles for the Marines melting in the tropical heat. Hatton and others were glad to pay; then the young merchants disappeared again.

In the years since Vietnam, Hatton has studied gong fu (kung fu), a martial art that uses the energy of combatants against them, and has read the Tibetan “Book of the Dead” many times.

Immersion into Tibetan Buddhism feeds his spiritual side and calms his anger: anger at the wrong-headed, even “insane,” involvement of U.S. troops in Vietnam; anger at the injustices and genocide of North America’s First Nations and Native peoples, whom he worked with on economic development for his second career; anger at his once-strong body, one that boxed and played football during his teen and early adult years, now imprisoned in paralysis and requiring others to help him care for himself.

When he began Buddhist meditation, Hatton says, “it was my first spiritual experience apart from drugs.” The Roman Catholic training he experienced led him not to spiritual higher planes but to disputations—a life-long leaning. “I always thought I was on the side of the angels, the good guys,” he says now. But learning Tibetan Buddhism, striving to see both the outward appearance of things and the inward truth of interactions, brought him to a new level.

Many Vietnam veterans just left the war behind and “got on with life,” according to an Army vet from the St. Paul area who became a priest and a professor at a Catholic college. (He prefers not to be named.) This vet and Hatton had debated at one time in the 1970s—Hatton for VVAW and the other for Veterans for a Just Peace. While initially somewhat dismissive of William Hatton in a phone call—“I’m not one of those professional Vietnam vets,” he said—he softened toward the end, to say how sad it was that Bill and others had to suffer difficult, long-term effects.

PTSD, a novelty in the 1970s, now is a term used to describe many people who have lived through COVID deprivations or other situations. Its meaning has been watered-down, Hatton says. Once he found out that there were other veterans like him, living with the war still going on inside of them, he didn’t feel as alone. Not everyone survived the post-war trauma. A few of his Marine Corps friends, once they were back in the States, threw themselves out of windows under the influence of LSD and deeply buried pain.

He remained traumatized. On a hunting trip in Canada with some local government leaders, he took up the rear as they stalked elk. At night, he insisted on sleeping with his hunting rifle, which made a few in the party quite nervous. Walking with guns, he had been thrown back decades, to Vietnam—even in a very different landscape with another kind of men.

Another time, living alone in Canada because his third wife’s chronic disease made her ineligible to emigrate from the U.S., Hatton started building inside his apartment “hides”: blinds where he could hide from whomever was coming after him.

But even dealing with suffering, Hatton had something to give. “So much had been taken away from the Native people,” Gajena says; Hatton could help. From his time in economic and community development, he learned the satisfaction of adding value to people’s lives, in Minnesota communities and more remote Canadian ones. And doing good was something he had been compelled to do, even when planning another Woodstock on the prairie.

Now his involvement in promoting peace is practicing his Buddhist dharma, his prayers for the world, for others, for the nuns, for everyone.

Outside his room, there is a dramatic sign, glaring yellow text on a red background:

“This property is protected by a United States Marine who is seriously lacking in negotiating skills, but is an absolute terror in combat.

“If you do not belong here, please leave.

“Negotiations are over.”

This sign reflects how he came into the Minnesota Veterans’ Home, bitter and twisted. At first, he bemoaned his placement: “They think they are doing such great jobs for veterans: Why don’t they make me walk again?”

At the time, he was “driven by anger over which I had no power. . . . What could I do? I could pray.” And his commitment to Tibetan Buddhist led to years of reflections on his faults and his reflexive anger.

Now, he says, he has a sense of gratitude. “I realized if they couldn’t give me my fitness back, they are doing a great job.”

Directly inside the door, a banner someone printed for him proclaims:

“Until enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.

“After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.”

His thangkas have been decorated by his teacher, Lama Yeshe, with prayer scarves of bright yellow, orange, and white. He is cared for; and he cares not just for a cause but also for the people.

Says Lama Yeshe: “Tibetan Buddhism is on one level incredibly complicated; one another, simple.” These followers of Buddha address the world of appearances versus the way things are—and the two are not different, he adds. “They are two sides of the same coin.”

The disciplines that he has shared with Hatton, Lama Yeshe says, “prepares you to die and prepares you to live.” And perhaps in these last five years, Hatton’s sinking into a different peace, an individual refuge, finally has cut off the tail of Vietnam.